how i think about and use AI : part one - bicycles, centaurs, and you

magic

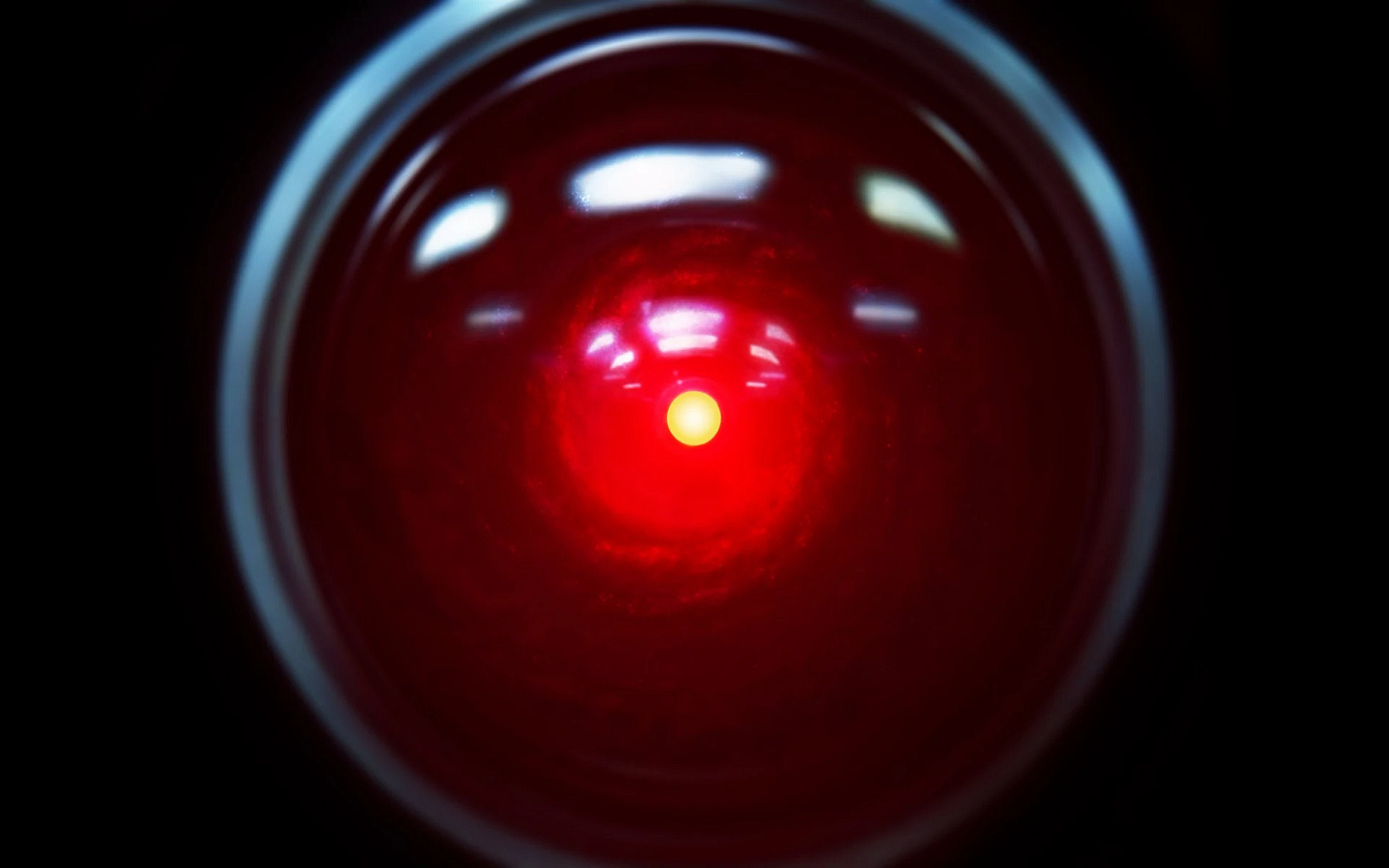

“any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic.”

— Arthur C. Clarke

does AI scare you a little?

the first time you use something like ChatGPT or Dall-E, you’re astounded. you can’t believe what you’re seeing. it definitely feels like voodoo magic. and that can be a little terrifying for a species prone to fear the unknown.

learn a little more about it, and you find there may be some legitimate things to fear — environmental impact, economic impact, cognitive impact1.

but you also see its utility. so you try to use it. and you quickly learn it’s like many technologies — over-promises, under-delivers, prone to fail or make mistakes, doesn’t quite do what you want, expensive to gain access, hard to learn, confusing options, and on and on.

at some point you’re less scared about it and more overwhelmed by it.

whether you’re afraid of it or frustrated by it, i hope to de-mystify it a little in this series and offer a framework for thinking about it, including some real ways i use it daily.

this series has been brewing for a long time, and touches briefly on a lot of information. it’s a kind of anthology of a lot of my current thoughts about what’s out there, and i hope it’s a good primer for those new to AI. if you think this would be of interest to someone, please forward it along.

full-disclosure: any time i try to think through the long-tail of where all of this is taking us, i’m unclear as to how it won’t kill us all in the end.

but until then, i have work to do. and AI isn’t going away. so i might as well use it — carefully and ethically — to make the world around me a better place, just like i do with every other technology at my disposal.

bicycles

there’s a classic Steve Jobs interview which shows his early vision for how computers would fit into the lives of people.

he says at twelve years old, he read an article where someone had measured the efficiency of locomotion of all species on earth. the condor rated highest — lowest number of kilocalories spent to get from a to b. humans were about 30th percentile, not particularly noteworthy.

but,

“somebody there had the imagination to test the efficiency of a human riding a bicycle. ‘human riding a bicycle’ blew away the condor, all the way off the top of the list.

and it made a really big impression on me, that we humans are tool builders, and that we can fashion tools that amplify these inherent abilities that we have to spectacular magnitudes.

and so for me, a computer has always been a bicycle of the mind — something that takes us far beyond our inherent abilities…”

tool users

humans use technology. we have for a long time.

“of course,” you say. but think about everything that is a technology, an invented thing for a purpose. yes, computers and industrial machines. but also concrete, chairs, chisels, the wheel.

Kevin Kelly reminds that the alphabet and language itself are technologies. devising systems by which we can communicate with one another — be it gestures, grunts, words, or Neuralink signals — was something humans had to develop and refine over time.

nearly all technologies are pretty inert morally. again, consider this technology we call the alphabet. with the alphabet, you can write a love letter or hate mail. a bard in Avon might pen one kind text that influences the world for generations, while a German political prisoner might compose another.

even more provocative technologies like a gun might be used with ill-intent, or it might be used for feeding a family via hunting or to aid in construction-related tasks via a power-actuated nail gun. people may debate other common uses, like self-defense, war, or law enforcement, but even then i think we can see these are arguments are related to the moral and ethical worldviews and choices of the humans using — and being affected by — these technologies more than the technology itself.

human beings use technologies. think about all the technologies you are using right now, just reading this. the device you’re looking at, the internet device that supplied your connection to it. perhaps your sitting at a table or wearing eyeglasses. you’re likely dressed in clothing (think about all of the technologies required to manufacture one clothing item you’re wearing and have it make its way to your closet). maybe you’re sipping coffee (in a ceramic mug, with a design on it) at a coffee shop that you drove to (on an asphalt road with painted lines), or maybe you’re at home (in a house) where you have a television on in the background (i can make you a detailed list of the kinds of technologies required to make that tv show if you like2).

and now along comes this new voodoo, this AI nonsense. what is it? how does it work? will it take over my life? will it solve all my problems? create new ones? and how do i use it?

it’s a tool and you can use it, if you understand what it is and its pitfalls.

and eventually it will fit comfortably into your life like your iPhone, your Subaru, and your Fruit of the Looms.

centaurs

Kevin Kelly wrote a book called The Inevitable. if you’re at all interested in technology or where the world is headed, read this book, and watch for his future observations.

i first became aware of Kevin Kelly from a 2007 TED talk called The Next 5,000 Days of the Web. at that time3, the World Wide Web was about five thousand days old (the Internet is older). he then laid out what he imagined the next 5,000 days would bring. this was not dreamy conjecture, but rather his wisdom about the trajectory of technology and the processes he observed already at work. when i encountered the video, we were already about a third of the way through those five thousand days, and much of what he astutely predicted had already begun to transpire.

so when The Inevitable came out, i knew i had to read it immediately. it identifies the twelve main forces that will inevitably shape our world in the years to come.

in chapter 2 of the book (COGNIFYING), he shares this story:

In 1997 Watson’s precursor, IBM’s Deep Blue, beat the reigning chess grand master Garry Kasperov in a famous man-versus machine match. After machines repeated their victories in a few more matches, humans largely lost interest in such contests. You might think that this was the end of the story (if not the end of human history), but Kasparov realised that he could have performed better against Deep Blue if he’d had the same instant access to a massive database of all previous chess moves that Deep Blue had. If this database of tools was fair for an AI, why not for a human? … To pursue this idea, Kasparov pioneered the concept of man-and-machine matches, in which AI augments human chess players rather than competes against them…

You can play as your unassisted human self, or you can act as the hand of a supersmart chess computer, merely moving its board pieces, or you can play as a “centaur”, which is the human/AI cyborg that Kasparov advocated… In the championship Freestyle Battle 2014, open to all modes of players, pure chess AI engines won 42 games, but centaurs won 53 games. Today, the best chess player alive is a centaur. It goes by the name of Intagrand, a team of several humans and several different chess programs.

But here’s the even more surprising part: The advent of AI didn’t diminish the performance of purely human chess players. Quite the opposite. Cheap, supersmart chess programs inspired more people than ever to play chess, at more tournaments than ever, and the players got better than ever…

If AI can help humans become better chess players, it stands to reason that it can help us become better pilots, better doctors, better judges, better teachers.

wisdom reminds us that new ideas are first laughable, then controversial, then progressive, then obvious.

so go ahead, laugh at the geeks playing around with it making pictures of avocado chairs and generating bad poetry.

then you might worry about the care you’ll receive from an urgent care doc who types your symptoms in a chat window before making a decision4.

but then you’ll find yourself praising the accountant who found an obscure deduction with the tools at her disposal.

eventually you’ll get annoyed at the attorney who looks through stacks of books in a law library when a query in an LLM (one well-trained on those same legal materials and more and with an active connection to LexisNexis data) would take mere seconds instead of hours (at $500/hr).

it will take time, but eventually this technology will be ubiquitous — like electricity, cars, and the Internet.

and personally, i believe the incorporation of machine-learning and artificial intelligence products into our life will be more disruptive than the car or the Internet. i have hope this disruption will be a net positive, but it remains to be seen…

coming up…

in part two, we’ll discuss in laymen’s terms how these chatbots work. knowing how something works often alleviates the fear of the unknown. it may create newer, more manageable fears, but we’ll take those as they come.

i include these linked articles not because i agree with them, but because they represent these understandable fears.

i charge $150/hr.

for context, the first iPhone came out in 2007.

↙️ YOU ARE HERE